I came across the painter, Thérèse Schwartze (1851-1918), a year or so ago. The piece I saw was a pastel of hers posted on Facebook. I was stunned and thought, Why have I never heard of this artist before?

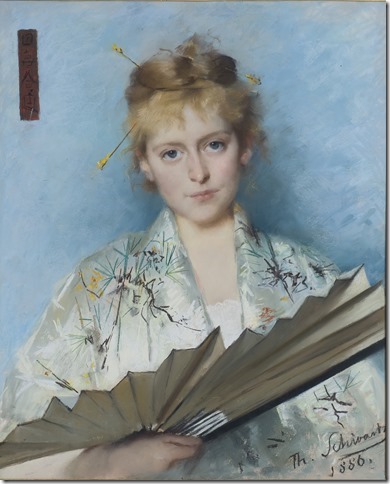

Have a look at the image I saw. Look at the bravura of stroke, the softness of skin, the sheen of fabric, the life in those eyes, those skillfully painted hands.

So then I began to track down more images, scrapping together bits and pieces of information. In doing so, I came across a wealth of material written by Cora Hollema and I discovered that she and another author, Pieternel Kouwenhoven, had written a monograph on the work of this artist (more information on this below).

My thoughts went like this – I can spend time and energy on cobbling together a blog post on Thérèse Schwartze OR I can approach Cora Hollema, the expert on this painter, to write a guest blog focusing on Schwartze’s pastels. What the heck – nothing tried, nothing gained. And to my absolute delight, she agreed!

One of the things I found so incredible was that this artist, this woman artist, made a great living as a painter. Extraordinary.

So let me hand over the reins to Cora Hollema. Go get a cup of something to sip on (coffee, tea, wine?) and settle in for some fascinating reading!!

(I should say here that all images are courtesy of Hollema. Many of the paintings by Thérèse Schwartze are in private collections and often when information is posted about work in private collections on the internet, it is incorrect. I am happy that here we can confirm the validity of the information about these paintings.)

~~~~

Thérèse Schwartze: Painting for a Living

by Cora Hollema

In her day, the Amsterdam painter Thérèse Schwartze (1851-1918) was a celebrated portraitist who combined talent and expertise with a head for business. She produced likenesses of the Dutch elite and members of the royal family in a notably un-Dutch style, becoming a millionaire in the process. Schwartze also established an international reputation, with countless exhibitions and commissions throughout Europe and the United States. The seemingly effortless brilliance with which she turned out elegant (and sometimes flattering) likenesses of her wealthy clients earned Schwartze much success, but also harsh criticism, especially from advocates for democratization and the renewal of society and art.

American Roots

Of crucial importance were the upbringing and training she received from her father, Johan George Schwartze (1814-1874). Truly a “citizen of the world,” born in Amsterdam to German parents but raised in Philadelphia, he had studied painting with no less a master than Emanuel Leutze before moving to Düsseldorf for further study. Like a modern “tennis father,” Johan began drilling Thérèse from the age of five; at 16, she promised to try even harder, so as “to be able to earn my living by painting.”

Their shared objective was highly unusual in an era when middle-class women were expected to marry early and well, relying only on their husband’s income. Thérèse’s artist-friend Wally Moes recalled that, “Because of her father, there was an American element in her character: she did everything on a grand scale and had a certain audacity that Dutch people tend to lack… If painting had not been in her blood, she would have undertaken something else and made a success of it with the same conviction and passion.”

In 1919, the Nieuwe Rotterdamsche Courant made a conservative estimate that Thérèse had produced approximately 1,000 works of art. This is a substantial number, even bearing in mind that her career spanned forty-odd years. Since this translates into an average of more than 20 works per year, we can assume that each commission took Schwartze approximately one or two weeks to complete. Such productivity appears to have been driven in part by her unflagging desire to provide for her extended family, especially since she had no husband.

pastel on paper, about 90 x 60 cm (35 7/16 x 23 5/8 in),

Private collection

Her determination is revealed by an experience in 1884, when Schwartze and Wally Moes spent four months in Paris painting, exhibiting at the Salon, and networking. On one visit, Thérèse used a moment of inattentiveness on the part of their host to ensure that they would not be late for another important visit. “On impulse,” recalled Moes, “without giving the matter a second thought, Thérèse swiftly crossed the room to the mantelpiece and put the clock an hour forward. Great astonishment on the part of the host, and profuse apologies for being so late.”

Even after she had become a millionaire, Schwartze continued working with undiminished energy. Her reasons may have been determined partly by her family’s history of immigrant entrepreneurship in the Netherlands, Germany, and the U.S. A strong will to succeed − and recognition of the very real possibility of failure or bankruptcy − were among their defining traits. This makes it easier to understand why Schwartze focused primarily on commissioned portraits, the sale and price of which were always fixed in advance.

Dutch Portraiture

The economic and cultural passivity that gripped early 19th century Holland was reflected in the period’s paintings. According to the historians Jan and Annie Romein, “the renewed middle class of the 19th century with its atmosphere of domesticity and its lack of fresh air, did not give rise to any fascinating new aesthetics.” The relatively modest demand for portraits was met by the sedate, skillfully painted images produced by the likes of Cornelis Kruseman (1797-1857) or his second cousin Jan Adam Kruseman (1804-1862), or by Jan Willem Pieneman (1810-1860). These were Schwartze’s precursors.

In the 1860s, however, the Netherlands entered an era of economic recovery, with a rapid expansion of trade and industry, banking, and the transport network. The country started to recover some of its faded international prestige, and the nouveaux riches sought to affirm their new status just as those with “old money” had done back in the 18th century – by commissioning more dynamic portraits. The time was ripe for an artist with Schwartze’s talents: her cosmopolitan background, combined with a flair for pictorial elegance and even ostentation, opened a new chapter in Dutch portraiture.

Schwartze’s early portraits are fairly subdued. Her stylistic development can generally be described as progressing from a meticulous technique using darker colors, borrowed from German role models like Franz von Lenbach (1836-1904) and Karl von Piloty (1826-1886), toward a lighter tone and more vigorous brushwork influenced by French and Dutch Impressionism. Until 1885 she worked exclusively in oils, then she gravitated toward pastels.

Pastels

The lighter tone that came to characterize Schwartze’s work over the years may have derived in part from her use of pastels. She started experimenting with them in 1881. Even her fiercest critics have praised her work in pastels, largely because of her virtuoso technique, with which she achieved stunning results.

It is not known who taught her this technique. Perhaps she taught herself, by studying artists who had used it in the past. Possible examples may have been a number of British and French pastel painters from the eighteenth century, especially Charles Howard Hodges (1764-1837), whose pastel portraits Schwartze must have seen hanging in numerous family homes. Working in pastels never took hold in the Netherlands and very few Dutch painters were comfortable in this medium.

It was the Swiss artist Jean Etienne Liotard (1702-1789) who achieved success in the Netherlands with his pastel portraits. He visited the country twice, in the 1750s and the 1770s. The itinerant court painter was fond of pastels, partly because of the speed with which they enabled him to work – a speed that suited his peripatetic life. Pastels were easy to transport and use, no palette was required, and it was not necessary to wait for paint to dry.

Schwartze may well have been attracted to the medium for similar reasons. Since pastels had fallen into disuse in the Netherlands, Liotard’s work has been compared to that of Schwartze. However, their techniques − and hence the results − are utterly different. In the main, Liotard has sharply demarcated surfaces and well-defined contours. He was precise and meticulous and hated loose brushwork.

In contrast, Schwartze’s work is characterized by the loose, painterly way in which she wielded the pastels. Face and hands are generally elaborated in great detail, and in those sections of the portrait she would apply color in several layers. But the clothing and background are often rendered in rapid, loose brushstrokes with the side of the pastels, so that the ground remains visible.

She had a genius for representing translucent tulle, frills, bows and other playful, elegant accessories of ladies and children’s garments with her pastels such that they appeared almost tangible, creating an extraordinarily seductive effect.

Pastel chalks were made using a technique invented in Italy in the sixteenth century: ground pigments and a water-based binder were molded into manageable sticks. They were initially used as a means of expanding techniques of sketching and draftsmanship.

This changed with the Venetian artist Rosalba Carriera (1675-1757), who was the first to start exploring the painterly potential of pastels, around 1700. When she visited Paris in 1720 at the invitation of a patron, she won instant acclaim with a pastel portrait of the ten-year-old King Louis XV.

From then on, pastel portraits enjoyed a vogue in France and other European courtly circles, and among the aristocracy. The bright colors, delicate effects, immediacy, and vitality that could be attained with pastels struck a chord with contemporary taste. There was a technical problem, however: how to fix the large surfaces of chalk. The best – though not wholly effective – solution was (and still is) to cover the work with glass. In 1745, Liotard met Carriera in Venice. Liotard’s patron in the Netherlands, the influential diplomat Willem Bentinck, commissioned a portrait from Carriera in Venice, in 1727, and another from Liotard in The Hague in 1755.

Prices

Since working in pastels was a faster process, Schwartze initially asked less money for portraits done in pastels than for those made in oils. But after the enormous success of the pastel portrait of seven-year-old Princess Wilhelmina in 1887, she changed her policy. Every self-respecting citizen now wanted his or her children to be regally immortalized in pastels. And Schwartze, who had a good head for business, responded by raising her prices. For a portrait bust – whether in pastels or oils – she charged between 1,000 and 2,000 guilders, while a portrait in three-quarters length, with hands, would cost around 2,000 to 3,000 guilders.

Given that Schwartze was producing at least twenty portraits a year, at an average price of around 1,000 guilders, we can assume that her annual income must have been at least 20,000 guilders. When this is multiplied by 20, we arrive at a present-day equivalent of some 400,000 guilders, almost 200,000 euros, or 225,000 USdollars.

Pastels: A “Feminine” Medium?

It is striking that Schwartze almost invariably kept to oils when depicting men. For women and children, on the other hand, she alternated between pastels and oils. Only two pastel portraits of men are known: they depict the landscape painter Paul Gabriël (1828-1903) and Salomon Druif (1866-1928), the Schwartzes’ family doctor.

Contemporaries saw this as a more or less obvious distinction. Since pastels could be used to convey “tender,” “downy” effects, they were ideally suited to portraits of women and children. “The tender properties of pastels served her very well, especially in likenesses of women and children,” and “A curious softness inherent to pastels, in consequence of which they seem preordained to render what is supple and downy, explains this preference”, according to some critics at that time.

In Schwartze’s hands, pastels certainly seem to become the perfect vehicle for making the soft, malleable, and translucent material of refined and sumptuous garments seem virtually tangible. And clothing is an important attribute for women and girls. This might appear a sufficient explanation for this remarkable feature of Schwartze’s work.

But why, then, did she scarcely immortalize any men in pastels? The few exceptions certainly produced fine results. What is more, working with pastels on paper may not be any easier than applying oils to canvas, but it is certainly a good deal faster. And since Schwartze charged the same price for both, she could make more of a profit on pastel portraits, since they took considerably less time to make. In view of Schwartze’s emphasis on generating sufficient income, it remains curious that she made so few portraits of men in pastels.

We can be fairly certain that the pastel portraits of Paul Gabriël and Salomon Druif were not commissioned. The painter Gabriël was an intimate acquaintance of Schwartze’s father and a friend of the family. Schwartze may well have made this portrait as a tribute and a gesture of her warm regard for him. She may also have produced it especially for an exhibition. After all, Gabriël was a renowned landscape painter, whose likeness was bound to attract attention.

Salomon Druif, the Schwartzes’ family doctor, belonged more or less to the inner family circle, by virtue of his position. This portrait too is unlikely to have been commissioned.

In other words, all Schwartze’s commissioned portraits of men were done in oils. The most relevant distinction between men and women, in this context, was one of social status. Could this be the explanation? Was a painting in oils worth more – in status, if not in terms of money − than one in pastels? And why would a portrait in oils represent higher status? First, it is undeniable that oil paints withstand the ravages of time more robustly. Pastels are more vulnerable, because of the problem of fixing them. However carefully a work is handled, the color will eventually work its way loose from the paper. Moisture is another potential hazard to pastels.

Did Schwartze affirm men’s higher social status by supplying a more enduring likeness, executed in oils? If so, she appears to have made one exception to this rule, with the portrait in pastels of the second most important person in the Netherlands. But that was in 1887, when the person concerned was only seven years old. Schwartze saw her as a tender, innocent figure with an almost Lolita-like tinge of eroticism: Crown Princess Wilhelmina.

Time Is Money

Working at high speed was one of Schwartze’s defining traits. In oils, she used the “wet-in-wet” method: the sections she was working on had to be completed while the paint was still wet, within no more than three days. The fresh appearance of her most successful portraits is partly attributable to this intensive method, and indeed many portraits were completed in a matter of days. Schwartze often referred to professionally made photographs of her sitters as aides-memoires, yet she always enhanced his or her dynamism to make the image her own. Though many late 19th-century artists consulted photographs, few admitted doing so because “purists” dismissed them as a crutch.

Her first biographer Willem Martin in 1923 notes that “The initial sketch would be laid in quickly amid continuous chatter, in which the painter herself would join in, with the somewhat absent-minded attention that followed from the nature of her work, or while [someone] read from an exciting novel or even the newspaper.” Schwartze was eager to ensure her sitter was never bored, so speed and cheerfulness were deployed to help foster an animated likeness. These qualities also seem to have been integral to her character: her contemporaries describe her as witty and entertaining, though to what extent she cultivated this impression is hard to say.

Schwartze’s high prices, flair for public relations, and active role in public life through various official posts elicited both admiration and resentment. She remained much in demand as the Dutch elite’s leading portraitist right up to her death in 1918, by which time—of course—World War I had changed the tenor of European art forever.

~~~~~~

Was I right? Fascinating stuff yes??

I’m honoured that Cora Hollema contributed this marvellous post about the pastels of Thérèse Schwartze. Let me tell you a bit about Cora and her book.

Cora Hollema holds a master’s degree in the social history of art. She works as a freelance writer and has curated numerous exhibitions, including a Schwartze show at Zeist Castle, Netherlands (1989-90). Having already published a Schwartze monograph in Dutch, she has just produced the English-language version, co-authored with Pieternel Kouwenhoven.

Here’s the front cover of the limited edition book:

The book is hard cover with a ribbon bookmark, is 184 pages, and has 118 illustrations with 82 in colour. It’s translated from the Dutch by Beverley Jackson. This limited edition of 500 copies has each copy numbered by hand from 1 to 500.

How to order the book?

[EDITED Aug 2022 – there is now a second edition of the book and the price, including shipping, is $50. I am assuming that is USD. And you can pay with a credit card at checkout.]

Go HERE.

Make a payment via PayPal and once the payment has been received, the book will be shipped within 2 weeks.

Prices (free shipping, registered) for USA, Canada, United Kingdom, and Europe:

USA: $70

CANADA: CAD$80

UNITED KINGDOM: £50

EUROPE: €60

I hope some of you will take advantage of this valuable offer especially as shipping is included in the price!!! Don’t wait too long as there are only 500 copies! What a treasure.

We’d love to know what you think of Thérèse Schwartze, her paintings, her life so please leave us a comment.

I look forward to hearing your thoughts.

Until next time,

~ Gail

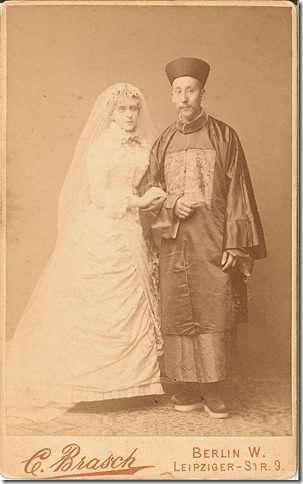

PS. (Added 12 March 2016) After this blog was posed, Cora Hollema sent me another pastel with some fascinating background info. Have a look!

Hollema writes:

Mia Cuypers (1864-1944) was one of the daughters of Pierre Cuypers (1827-1921), the architect who designed buildings including the Rijksmuseum and the Central Station in Amsterdam. In 1883, Mia fell in love, to the dismay of her family and the astonishment of Amsterdam’s “high society,” with the Chinese-British merchant Frederick Taen-Err-Toung (1859-1945) from Berlin, who was in Amsterdam selling his Oriental merchandise. She weathered the social commotion and married Toung in 1886, after first obtaining the bishop’s permission.

After their wedding in Amsterdam on April 27, 1886, the couple settled in Berlin, where their four children would be born. Frederick Taen was a successful businessman with companies in Berlin and Dresden, but this did not diminish the feeling in Mia’s family that she had married beneath her station.

Schwartze, who was a close acquaintance of the Cuypers family, was commissioned by the groom-to-be to make this wedding portrait. The Chinese characters in the upper left corner mean “rice field” (Taen), “longevity”/”delighted,” and “coming together.” The couple separated in 1897 and embarked on a protracted struggle for the custody of their four children. It was said within the family that Schwartze took just one-and-a-half days to make this portrait.

21 thoughts on “Thérèse Schwartze – Painting For A Living”

I’m not normally interested in portraits, because they are so often like stuffed shirts….but clearly this lady had an extraordinary talent, especially with that loose painterly approach….she would easily fit in with today’s way of working. I specially like the last one, her self-portrait, with restrained colouring. The perception that “oils are better” seems to have persisted to the present-day. Here in Britain pastels have nowhere near the same popularity as acrylic or oils…..except in the art classes.; almost everyone in mine uses pastel! People seem to think that pastels are somehow inferior and they are somewhat snubbed by buyers unless the artist has already got a name for him- or herself. Therese is also someone I’ve never heard of, so thank you for presenting this article.

Chris, I agree with you about how this artist worked – with her loose painterly approach, she certainly could be working today.

It’s so frustrating about how pastels are viewed. I think if they didn’t have to be protected under glass, it would be a totally different story!

Glad you enjoyed discovering this artist 🙂

Ook ik heb het verhaal met belangstelling gelezen, alleen wat later als deze posten van 2026. Het is nu 21 juni 2022 dat ik hier kennis van genomen heb. Ik ben er gister achter gekomen dat ik een zelfportret van Therese in mijn bezit heb. Het is heel leuk om over haar en haar leven te lezen.

Annet, thank you! For others, this is what she wrote as translated by Google: “I too have read the story with interest, only a little later than these posts from 2016. It is now June 21, 2022 that I have become aware of this. I found out yesterday that I have a self-portrait of Therese in my possession. It is very nice to read about her and her life.”

That’s marvellous Annet – so very exciting for you!! And of course I am curious as anything!

(I’ve added Google’s translation below – I have no idea if it is correct!)

Dat is geweldig Annet – zo spannend voor jou!! En natuurlijk ben ik nieuwsgierig als wat!

I was enthralled with this article. I usually have a short attention span and I tend to skim long articles but this one kept my attention and I will be reading it again and again. I loved reading about such a strong woman from those times. My favorite author is Jane Austen and this artist fits into that small arena. I now want to delve more into her life and art. Thank you for sharing. I can’t express just how much I loved learning about her.

April, I know what you mean about having a short attention span – I think this is a common characteristic of many of us these days. So I’m happy to hear this article caught your full attention (as it did me). I’m glad I we have your curiosity fired up to explore further. If you discover anything, I hope you’ll share it here.

This was fantastic reading and like you say, we never heard of her. I started doing portraits so I really liked this article. I have three portraits of pirates going in my show at Lunenburg art Gallery, starting May 24/16

So glad you enjoyed the article Rae and hope the work of Thérèse Schwartze inspires you in your portrait paintings! Check out her oils as well.

Wow, thank you for this, Gail. I loved learning about this (new to me) artist. So many of our artist foremothers are lost to us. I’m always happy to learn about those we do have information available on. Wish I could afford the book!

Oh you are so welcome! I am just so happy I could persuade Cora Hollema to contribute the article!

At least you know of the book’s existence – you never know, one day, you maybe able to add it to your library.

Thanks so much for introducing Therese Schwartze. I too never heard of her and was blown away by her work and work ethic. I ordered her book to study her further. Really appreciate your blog and information.

Best,

Victoria Templeton

Victoria, how wonderful that you have bought the book! I’m delighted to have introduced you to this fabulous artist.

And thank you for your kind words.

Wonderful post Gail. Ms. Cora Hollema has done a masterful job of presenting this artist who might have remained hidden without her research. Therese Schwartz was an original, independent way ahead of her time and I love her style. Her self-portrait, done just one year before her death, speaks volumes about her attitude! Her children’s portraits are endearing but I wonder why she deliberately used black with her study of Henri Knap – perhaps he was a bit of an challenge as a sitter…? Salomon Druif’s portrait tells a lot about his personality – his hat! His Scarf! His gaze! The way he holds his cigarette – a strong character, a Bon Vivant. This was a treat, thank you.

Yes, kudos to Cora Hollema for taking on the task of revealing this artist to the rest of us!

Thanks for taking a close look and making specific comments. I hadn’t thought about Schwartze’s use of black in Henri Knap’s portrait. Keen observation!

And I agree about her self-portrait. She also did a fabulous self-portrait in oil in 1888. Instructive to compare the two.

Wonderful. The people in these portraits are alive. Thanks.

They are aren’t they?! Thanks Jean.

Thank you for this article! I am a relative of Therese Schwartze trying to research our genealogy. Do you happen to know what religion Therese was? There is great mystery as to whether there is Jewish ancestry and little is mentioned regarding Therese’s heritage. My mother’s maiden name is Schwartze and she is a distant cousin of mine. Thank you!

Hello Jessica, How fascinating that you are a relative of Thérèse Schwartze! I do not know the answer to your question but I have sent it off to Cora Hollema, the author of this article, hoping she may have an answer for you!

Dear Jessica,

No jewish ancestors are found in the case of Therese Schwartze. She was ‘Luthers-Evangelisch’, so protestant, as were her German ancestors from Vlotho (Germany). I checked the archive of Vlotho.

Thanks for asking!

Yours sincerely,

Cora

What a gem of an article. Thank you both, Gail and Cora, for the research and posting. She might have become one of my favorite portrait artists of all time.

Alex that’s WONDERFUL to hear!! I was so glad Cora agreed to guest post. I hope there are still books left!