I may as well come right out and say it – Albert Handell is one of my pastel heroes! I’ve followed and been inspired by his pastel paintings whether I’ve seen them in magazines, social media, his books, or, on rare occasions, in art galleries. I also was lucky enough to see Albert demonstrate at the first IAPS (International Association of Pastel Societies) Convention I attended way back in 2001 in Santa Fe.

In my IGNITE! art-making membership, we have a category called Blind Date (which happens whenever we have a fifth week in the month), and as the name suggests, the content can be anything! So I decided to surprise members with an interview with a well-known artist. And as Albert and I had been working towards him doing a blog post for HowToPastel, I thought we could accomplish two goals in one go.

We set up an interview over Zoom and chatted away. I had specific questions but we also followed the conversation wherever it wanted to go. That video interview is in IGNITE! The edited transcription tidied-up to fit with some questions along with accompanying images is here, right now!

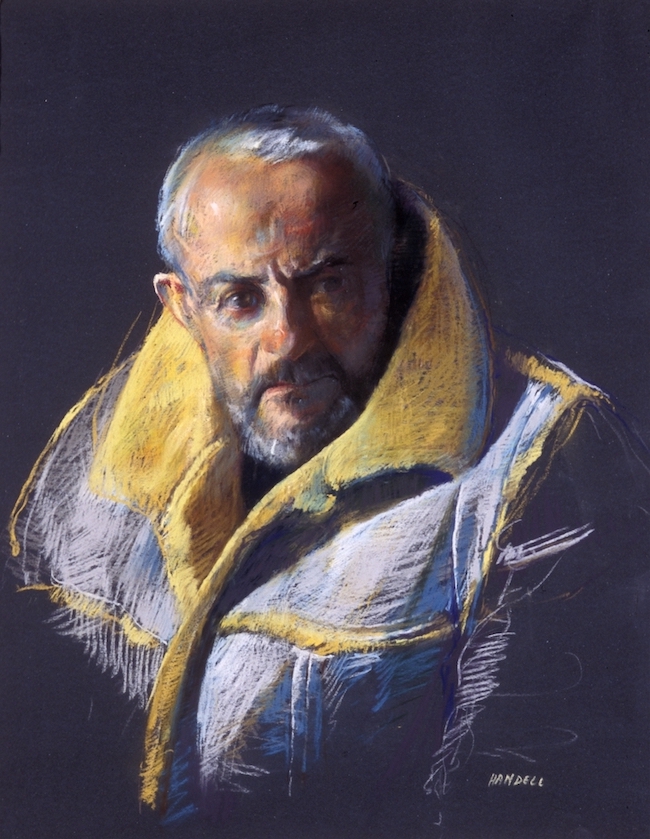

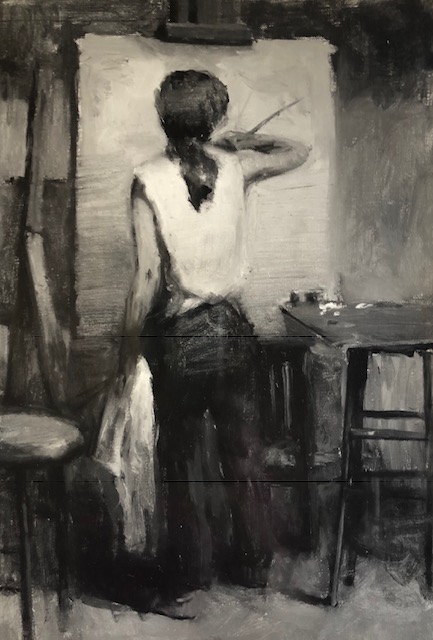

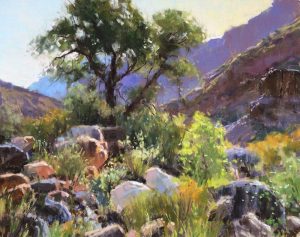

Don’t know Albert Handell’s work? Here’s a sample:

Before we get going, here’s a very short bio from Albert Handell!

Albert Handell Bio

Albert Handell writes, “I have had an extensive career as an artist..with changes along the way. Parts of me wish I could still pastel every different interest that at different times fascinated me. But alas that is not to be.”

Be sure to visit Albert Handell’s website HERE.

Now let’s get into the interview! It’s long and fascinating so settle in with your favourite beverage and listen in while I chat with the Master!

*****

Gail: I know you love to dance! How does that relate to your work?

Albert: I love your question about dancing. So I’m an old swing dancer. I like the music from the fifties and I know the steps. I also like to do freestyle dancing. So I like to dance. Yeah. I like to dance with somebody who knows what to do and likes to separate and just feel the beat. And I’m all about the beat. If you give me music from the forties, that’s not my beat. And the fifties is, you know, Fats Domino, Jerry Lee Lewis, and the whole bunch there. And, I feel the beat. If I don’t feel the beat, I don’t feel like dancing. I mean, my feet might move and I’m sitting, but once I feel the beat, I can’t sit still. And it has to be the fifties. So there’s an intuitive aspect that has to do with feeling the beat. I really like to move with it. When it comes to picking out a subject, it’s about intuition.

Okay, let’s start right in. How do you go about picking a subject to paint?

Well, it ties into the idea of intuition. Let me show you what I mean. Let’s say there’s a waterfall somewhere. And it’s not a long drive. You know, some people could drive for three, four hours and then paint. I can’t. If I’m going to paint in Taos in the morning, then I drive up from Santa Fe and sleep in Taos. I don’t drive an hour and 15 minutes and get burnt out on visuals on the way. I like to be fresh. So I’m parked in the parking lot for the waterfall. As I’m walking towards the waterfall, suddenly something hits me. And my mind says to me, something out there has touched something inside me.

So why should I be attracted to whatever it is? Let’s use that word – “attracted.” If you are attracted by a guy or a gal, do you analyze why? You just say, “Oh nice.” So my job is, with pastels, to go figure out what’s going on out there in relationship to me. So that’s where I paint. I don’t go to the waterfall because the waterfall is a decision that has to do with my head. And that’s fine. But as I was walking towards it, something hit me. That’s more important, the intuitive response. So that’s the first thing. Dancing and painting.

When you don’t know what to do next on your painting, what do you do?

In chess, when it’s your time to move, you have to move something. And if you like the position and you don’t want to disturb the position, or you don’t quite know what to do, you make a minimum move. You “push pawn.” That’s as close to nothing as you can do in chess. If you’re painting and you’re confused, you’re not inspired, or you’re unclear as to what to do next, “push pawn.” Drop the brush, drop the pastel!

Now let’s say you’re doing fine and after two hours, you know you don’t want to work anymore. You’re not sure what the hell’s going on. Take the pastel or the oil painting and place it against the wall, facing the wall. In other words, you’re seeing the back of the piece. The next day, as you turn the picture around, don’t look at it. Take three or four steps away. Turn around. Yes/no! If it’s yes, you probably have a finished picture or very close to a finished picture. You may need to start doing this and that, but very little of this and that, cos too much of this and that and the carrying power gets weaker, the freshness gets weaker.

How do you respond to this question from students: “When is a painting finished?”

My answer is when I don’t want to paint on it anymore. But they are glued to their canvases. I mean they don’t step back. They don’t realize that ‘carrying power’ is the most important part of a painting, in my opinion, not the details. The details compensate or add to the ‘carrying power’ or don’t bother with them. So that’s what I tell my students. But there’s no getting them to step back even three steps. I mean they’re glued. So I tell them, work the best you can.

Tell me a little about your early life. Did you draw and paint as a child?

I grew up in Brooklyn. I used to draw on the sidewalks. For 2 cents – you know I’m 83 right? – so we’re going back to when I’m seven or eight years old. So you count the years! Anyway, there’s a luncheonette or a candy store, whatever you want to call it, and for 2 cents I could get three pieces of white chalk. For a nickel, I could get three colours. I was set! I was safe, sitting on the floor and making all these drawings. I couldn’t fall down, you know?

How did your childhood influence your artwork as an adult?

When I would look up from drawing on the sidewalk, I would see a storefront. Well, if I looked across the street, I would see a grocery store where I’d see a guy with barrels of pickles standing in the doorway. So I’m used to panning in. There were no mountains or fields in Brooklyn, it was the city. So I like to do parts of buildings. I’m used to measuring the architectural part of whatever I’m painting. I like correct proportions.

Talk a bit more about measuring.

I’ve done portrait work. Portraiture is measuring otherwise, forget the likeness. Now my students don’t understand measuring. They don’t understand two things. Measuring and stepping back. So they play around with a tree or something where there’s no architect involved. It could be anything you know? They hate doing a building because the building does call for some measuring. Correct measuring but without it being sterile.

In other words, I believe in measuring. How far away is the bottom of the window from the top of the door? That’s a measurement. And I want to get that stuff right, but I don’t want it to be an architectural drawing. Architects give you the whole building. I take part of the building and I put cast shadows on it. I love that, you know, how the white of the window pane goes into shadow and all that. So they don’t understand measuring and they don’t understand carrying power. Two essentials in my opinion.

One of the things you’ve mentioned is the idea of a painting having ‘carrying power’. Can you go a bit deeper into what you mean by that?

Sure. When you’re not looking at the picture and you stand back three feet and then you look at it, it either hits you or doesn’t.

You have a choice of carrying power or detail. What gives a painting carrying power is contrast. Design. It’s not the details. For the details, you’ve got to get up closer. Design is the light effect. Yeah, I would say it’s the light effect and the placement. Placement to me is composition.

Let me tell you one thing about colour. Say we’re outdoors painting something. If you have value contrast, that’s what grabs you. But if you don’t have value contrast, then you gotta have different colours of the same value and I make a lot out of that.

Also, pastel is an opaque medium and I have my watercolour underneath it is as transparent as you can get and I like textural contrast as much as I can do. I can do more with oils with textural contrast. You know, the thicker stuff sticks while some of the thicker stuff in pastel might not stick. But the watercolour, I leave some of that to come through.

I use two colours from my watercolours: Payne’s Grey, which I think in watercolour is drop-dead beautiful and it’s a cold grey, and Vandyke Brown which is a warm brown between Burnt Sienna and Raw Umber and is warm compared to Payne’s Grey. I just use those two and I work from dark to light in watercolour.

I apply a few pencil marks within two minutes. Then reestablish some of the pencil marks with the Payne’s Grey, nice and dark and everything else floats around it. That’s it. Then I go to the center of interest and reinforce the darks because they get lighter when it dries. I work on my pastel from the center of interest out and a lot of times some of the watercolour just stays there. And there are sometimes watercolour accidents, which adds to the textural quality of the picture. So that’s what I like to do. In oils, the textural quality is wider. Yeah.

Let’s say it’s some kind of a blue-grey barn door, with some dark panels here and there. I like to use other colours. Let’s say it’s green, you know, summer. That’s better yet. It’s dark green and lighter green, and all that with watercolor underneath it which is Payne’s Grey or Van Dyke Brown. I like to take a reddish colour, the exact same value, and put a little bit into the large area over the dark greens. Now the greens look far more complete. I could also have used a purple.

You started in oils. How did you move from oils into pastels?

So, I come back to Brooklyn from France and I’m going to have a show in September 1966 at the ACA Gallery, which is a pretty big gallery in New York City. And, what I would do is paint every day. I’m serious about that. And after three months I was all burnt out. The well was empty. And I went a little crazy. I had nothing else to do but play volleyball. I like girls, you know, but it was all about painting and drawing.

The idea of waking up and not painting was not on my agenda. So I didn’t want to waste three or four weeks until the well filled up again.

I like to draw a lot. And someone said something about pastels. So I call up my friends who worked in pastels for information – Burt Silverman, Harvey Dinnerstein, Daniel Green, Aaron Shikler – and they said buy this, buy that and so I got going in pastels. I purchased a large set of 350 colors of Rembrandt Soft Pastels. I started working with them on toned Canson Mi-Teintes pastel papers. This was in 1965. It was a relief!

And it was like I was a fish out of water. Oil is a glossy medium. The resinous darks are very easy to get as compared to pastel. And the lighter colours look chalky. With the pastel, it’s a matte medium. The high key colours are very rich and it’s the darks you work your ass off to get.

And it was also like a fish going into water. When I went into pastels, I was a well-developed painter going into a different medium and it was like, how wonderful. Yes. It was different. It meant exploring some things, but what’s the big deal? Explore!

And when I had my one-man show, the small gallery had the pastels, and the big room had the oils. And you know what? I couldn’t own up to it then but I preferred the pastels. So that’s how it began.

You were in France? What took you there?

I lived there, mostly Paris, for four years, from 1961 to 1965. I speak French, by the way.

Well, I’m in New York. I’m a New Yorker and I used to go around with a sketchpad and I go to the village and go to the Café Figaro and you know, I’m a young guy and there are other young people from the university – NYU is right there. And, you know, I attract some attention. And then I’d say, “I like realistic painting.” And they flipped back in horror and say, Don’t, it’s already been done. So I heard that stuff too often and I decided, well maybe I’ll go back to where it has been done. So I decided to go to France. The nice thing about that is that I was away from all the tapes that were playing in my head.

I was able to work with smaller brushes. I liked smaller brushes. You’re supposed to work with bigger brushes. I liked using transparent and opaque. You’re supposed to bury the transparent, make it all opaque. I said forget that. So off I went to France.

Tell me about beginning to use pastels en plein air

I did a lot of work indoors. It wasn’t until I moved to Woodstock, New York that I started taking pastels outdoors. I lived in Woodstock from 1970 to 1983. The only person who was working rather regularly and beautifully with pastel outdoors was Wolf Kahn. And God bless him, he did a beautiful job.

In Woodstock, I had these pine trees all around me, so I said, I’ll go outside. And that was the beginning of the end for me. I got involved with it and then Wolfie, when I met him, he didn’t give workshops in pastel, he gave them in oils and the only person I know of back then, 45 years ago, who was giving workshops in pastel on location, en plein air, was yours truly. I started that thing. I mean, Richard McKinley, I mentored him. And look how beautiful his work has gotten.

Did you know that painting with pastels en plein air wasn’t a common thing? Just think about it for a few moments. Every now and again Manet painted something outdoors or Degas did some horses, but they were basically oil painters.

You take Wolf Kahn who’s very much an oil painter. He also did beautiful pastels and quite a few of them. So he really qualifies as compared to Monet or Manet, okay? Are we on the same page?

For outdoors, portability was a drag. I figured that out and you know, who was very helpful? The Heilmans – John and Marge Heilman. Marge is an artist. She studied with me. She’s from California. And John is an engineer who hates retirement. So between them two, they put together the Heilman box

Now they’ve been copied. So I think the Heilmans deserve credit because before they came up with that box, well I don’t want to think about it! I take pleasure in telling people through my workshops. I presented it to the country and now it’s commonplace. So I want to whisper that into your ear.

And when I go to give a plein air workshop, I carry my Heilman box onto the plane. The last thing you want to do is have them open this thing up, look inside and not know how to close it. So pack the watercolours and any tube of paint but carry your pastels onboard.

Wolf Kahn, he started a few years before me and never taught in pastel. The way he went out en plein air with pastel is he had a little tin can. He opened it up and he did his work in 10, 15 minutes. He did beautiful work.

With me, it’s a whole story with opening up the easel. It’s like what Richard McKinley does but he’s very organized. He has it all laid out just like that. I have it humble-jumbled. If I have it all laid out like that, my eyes go to sleep. I used to have it laid out like that, but I have to go for it, guess at it, feel it. If it’s a little bit too red, I go lighter, and then it’s not too red. So I am flexible with my application of the pastel, more so than anybody I know.

Okay, I’m going to change direction here. What do you think is the greatest challenge to an artist actualizing his or her potential? What are the obstacles?

Lack of practise. Yeah. Lack of practise. You gotta paint regularly. Stay on it. It’s like anything else – you need to practise. There’s so much low standards in painting these days. The magazines write articles about just about anything and, well, then people think, I can paint like that. And I can understand. And they’re dying to paint a good picture. Yet they only paint once a year or so and they only paint at workshops. Well….. They have to have some clear instruction and they have to practise it.

When I help my students, I give them a choice: I can work on your subject or not, it’s up to you. Some people say ‘Don’t touch,’ while for most, it’s fine. So, they have a problem on the upper left, whatever it is. I help them on the upper left then they say, what about the lower right? I say, ‘Look, why don’t you absorb what I just did on the upper left? Don’t just take it for granted. It’s like the piano, you know, boom, boom, boom, boom, boom, boom, boom – that’s the C scale. Ohhhhh! But that doesn’t mean you can play it just because I showed it to you.

We have to practise it and then go back. So when I do whatever it is in the upper left, practise it. Don’t just go to the right side and call me. They’re dying to finish a picture. They don’t paint as much as I’d like them to. So when they do paint, they have to finish the damn thing. If I have a student who’s for real, they’re willing to do the work in between workshops. I tell them, work on three or four things at a time. Get a fresh look at what you did three days ago and see what your reaction is. In my opinion, if something has to be bigger, just make it bigger. If something is too bright, pull it down. Oh, and when something’s too bright, don’t just take it out, pull it down so it’s not so bright cos sometimes the thing is good but it’s just too bright. It doesn’t have to be totally thrown out the window.

You can’t just watch a teacher do the C scale and that’s it. That’s not it. You have to learn something that’s comparable to the C scale and then you have to utilize it and get it. And then after you get it, you come back and learn something new. Then you practise that. Then you do the left hand, that’s new. And then you come back. And then you do both hands and practise it until you can do it. Students aren’t able to do this. A lot of these folks, God bless them, are retired lawyers and the kids are out of school. They did some art in high school or college or something and I’m touched. They deep down want to be an artist, but they were afraid to take a chance.

Yeah, I think they go to the workshops because they can’t stand living with themselves. In the old days, I used to call it D D D – desire, determination, and disgust. That’s what it was for me. I had the desire, I had the determination, and I would have been disgusted with myself if I didn’t do what I had to do. I couldn’t live with myself. It was like a healthy sickness.

Oh, here’s a tip to help understand problems in your work. If you’re working out in the sunlight and you have an iPhone, take a photograph of the subject every 20 – 30 minutes, cos it changes. At the same time, take a photograph of what you’re working on. So that after three hours, you can analyze what you’ve gone through. It’s a great idea. I got the idea from when I first did step-by-steps 30, 40 years ago now, but I can’t get them to do this. If you’re working indoors from a photo, you don’t have to photograph the subject, but you should photograph your painting. Then you can analyze it because many a-time, things are going fine, and then they’re not going fine. And that’s the point where you want to understand what the problems are, whatever they are.

What were a couple of the key milestones for you in actualizing your potential as an artist?

Okay. For me, it was going to the Washington Square outdoor art show and seeing those realistic painters.

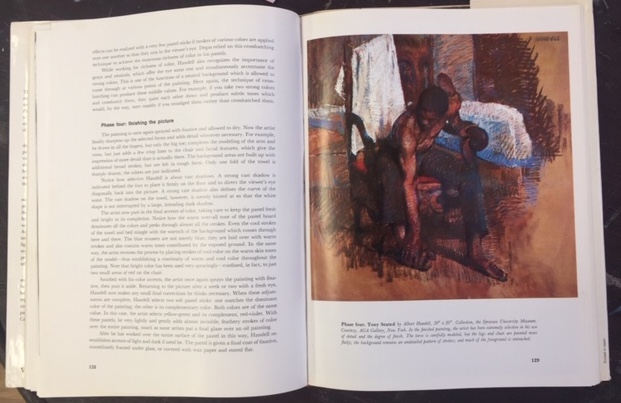

And then, the other was being in a book. The director of the ACA gallery knew Bill Holden, the editor of Watson Guptill Art Publications. They were revising a book by Elinor Lathrop Sears called Pastel Painting Step By Step. Dan Green was in it, Burt Silverman was in it, Harvey Dinnerstein was in it. I was in it! And when that came out in 1968, overnight, it changed my life.

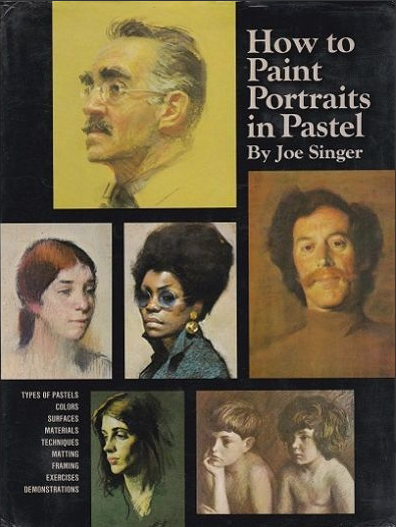

It’s funny what happens when you’re in print. I became an expert in pastels, certainly. I became known to some people as one of the five top pastelists in the country. I also had a number of pastels also in their next pastel book, Painting the Portrait in Pastel by Joe Singer, printed 1972, and then in How to Paint Figures in Pastel also by Joe Singer.

Interestingly, all the works in those three publications were studio works. I painted a lot of portraits and tried two or three commissions. I found they weren’t for me and I’ve never taken a commission since. All the portraits were done of people who have visually attracted me and I asked them to sit for me.

I also had a substantial article in American Artist magazine and that also put me on the map. By that time, looking at the magazine right now, there were plenty of pastels in that article.

Were there any other milestones along the way that influenced you?

Okay. When I was 16, I went to the Art Students League on Saturdays and learnt about drawing. and I had a George Bridgman education. I learnt how to draw from the figure. I learnt light and shade. I learnt measuring. I started on Saturdays drawing and I always worked a little bit indoors and I did a little watercolor stuff or other outdoors.

I lived for Saturdays. I don’t know how else to put it in. Then when he died, I was 19. I didn’t know what to do until one of my classmates who had started painting before me, his name was Jim, took me to the outdoor Washington Square outdoor show. Boy, that was it. That’s what I wanted. I mean, I was flabbergasted, what can I tell you?

It sounds like you knew from early on, what you wanted to do and what you were here to do?

Oh, I didn’t know where I wanted to go. It came together when I saw those paintings. Wait, let me take you back.

Well, Brooklyn was far more provincial than it is today. And I liked the magazines that I saw and when I went to the movies, they had these marquees that were done by artists and I wanted to be one of them. They had to explain Fine Arts to me. You paint what you want, then you sell it. I thought it was hysterical. I thought it was absurd. I guess I wanted to be an illustrator – I considered that to be art. You know, they want something, you paint it, they pay you, then you go on to the next one. But back then, a lot of painters had it hard. Photography took over. I mean there was a point there when Norman Rockwell didn’t have any work. Yeah. Photography came in the fifties. And that was when I was up at-bat. So one of my teachers took me to a café and we were talking, and he explained to me about Fine Art.

I said, what’s Fine Art? He says like those guys, pointing at some characters sitting nearby talking. Then I went to the Washington Square outdoor exhibition where there were some good paintings by Rudy Colao and Walter Brightwell. They looked lovely to me. I said, I want to do that. It wasn’t that I knew what I wanted to do and I didn’t know where to go. I really didn’t know. I was a little lost.

So I started studying with Rudy Colao and I worked with oils for quite some time. I only got going with pastels when I came back from France.

My father was a Russian immigrant and he was so disappointed in me. He came over steerage class, couldn’t speak English. The immigrants, they went through the shit so that their kids had a shot at it. And here I am throwing it away or going back to Europe for four years. He couldn’t understand that I wanted to be an artist. I had an overly good relationship with my mother, she was intelligent. She said if he’s happy, leave him alone.

How did you end up in Santa Fe? For as long as I have known of you, I think of you in Santa Fe.

Well, Woodstock, New York had terrible weather. It was a bit lonely but I got a lot out of it. I kept hearing about the Western market and this, that, and the other thing. Taos and Santa Fe. So I gave a workshop in Riodoso in Southern New Mexico. And I did that so I could go and see Santa Fe and Taos, see what that was all about.

After the workshop, I drove up to Santa Fe with my son’s mother. At the time, we weren’t married and there was no son yet and I go into Santa Fe and again I thought it was just drop dead beautiful. I was going up there to go to Taos but I was sitting on Canyon road looking at the adobes and the amount of green. See, adobes are warm. They complement the greens beautifully. And in Santa Fe, it’s not over-ridden with green, you know, like Woodstock was. And the skies, the smells, the clouds, everything. Everything. I was bowled over.

Then I went up to Taos. It’s very nice. I liked both places. That was about 40 years ago. And, then a year later, with my wife at that time, we went to the Monterey peninsula and oh, those windswept trees. And I was beautiful. I loved it. The problem with the Monterey peninsula? Traffic. I’m not crazy about traffic. You know, as a New Yorker, I didn’t have a car, and oh, all these highways. And then I went to Sedona, which I also thought was drop-dead beautiful. And then I went to Santa Fe and Taos. And I kept saying to myself, the ocean, the skies, the oceans, the skies.

But to feel the ocean, you’ve got to stand by the ocean. You walk away from the ocean, you can smell some salt. But the sky, you just look up. It’s always there. So not the ocean. I was undecided between Taos and Santa Fe, and my wife at the time – we were going to have a kid – she looked at the schools and she said, Santa Fe is much better. So I said, fine. They’re right near each other. And I did spend a lot of time in Taos painting. I did workshops there also.

The market, you know, in Santa Fe and Taos, they like realism. Oh I don’t want to do Cowboys and Indians, but I paint realistically. New York was ridiculous. It was absolutely absurd. And Woodstock in the wintertime, you got cabin fever. That’s where I did a lot of dancing. The whole problem with Woodstock is the musicians. They started at 11 at night and then played and danced until two or three in the morning. And you know, when you get finished dancing after two or three hours, I couldn’t sleep, so I had to re-adjust my painting time!

I’ve known you’ve had a relationship with nature, a feeling for nature, it’s obvious in your work. Can you speak to that?

As far as nature goes, in Brooklyn, you don’t have a waterfall. You know, it’s not nature. It’s a city. What I like about Woodstock, New York, is it was a small town. It was out in the Catskill mountains. And as I got involved with nature, as far as I’m concerned, the trees reminded me of my mother. I got along just fine with her. The rocks felt like they got in the way of what I was doing and that reminded me of my father. And the water reminded me of me – – nothing was going to stop me. So that’s psychological, but ahhhh….

Ah, another thing, back then, I was working with pastel on location. I had to paint every morning. Period.

And it’s June and it’s green all over the damn place. So after the morning painting, pastel or oil (now it’s just pastel), I closed up everything. I had a water canteen and a sandwich and I started hiking around the stream bed. I don’t like mountain views and all that. I don’t want to paint them. I like to paint close, panning in like the storefronts of my childhood. Okay. Right. I walk for hours for the rest of the day. Suddenly there was no sun. I was in a green room. That was amazing. And I saw some cool purples and that gave me an insight. That gave me a real insight.

I knew when you had the sun out the colour went away. When you had just a little bit, or you had a no sun day, a grey day, you had, instead of light green, dark green, and middle tone green, I had these greens and I had them changed into purples. Well I like to use the word mauves. I don’t know if that’s English or French. Purple’s. Cool purples. You know purple is blue and the more reds the warmer, and the more blues, the cooler.

Tell me a bit about your teaching and workshops

You know, I never had a job. Actually, I should clarify that. I was asked to teach for 11 weeks at a university, so I had a job for 11 weeks. In the end, I had 22 weeks of a paycheque, you can quote that. I never had a job.

I always like to teach, not in high school and university, that’s a joke, but you know, individuals, for instance at the Art Students League.

So my workshops…let me clear this up. I paint for the first two hours. I don’t turn around and talk to the students. When I paint, I talk to myself silently. And when I demonstrate, I open my mouth. They don’t ask any questions. They sit there and when I’m done, I take any questions they have.

At first, I was sweating it cause I’m private, you know, and I really didn’t know how to articulate that well. When I first started demonstrating it would be blah, blah, blah, blah. You know, you’re by yourself, you know, for so many years. Now I’ve been demonstrating 40 years. What am I, 84? I started at 47 or something like that. And so I paint. If I had to give up painting to teach, I just wouldn’t teach. I happen to love teaching.

The nice thing about workshops, well you know, you have to make some money. I don’t come from a wealthy background. I liked teaching my workshops. You know, I’d make enough money. Then I come back to my studio and have a fresh view on everything I’d left and that was healthy. So healthy. It was another activity.

Nobody had to study with me. They all wanted to. That’s a big difference. In the university, in the morning I’d have the seniors and we did nice things. We made pastel in my studio. We did a lot of things. Then in the afternoon I had this freshman class and I didn’t know what to do. I said, what do you do with them? They said, Oh, you inspire them. I said no, I don’t inspire people.

I remember when I was teaching pastel at Woodstock, New York, I had to have a pastel store in my studio. That’s because if the students had to buy the pastels that I wanted them to have, they wouldn’t be able to do it and they wouldn’t come. So I said, I always say, bring whatever you have and I have everything you need. I had the papers too. I had the store. Well, I had no choice about it. Either I don’t teach pastel or I have the materials there. You don’t want to frustrate your students.

And by the way, I have an open studio policy. When I was younger, I wanted to be invited to this artist studio and I was afraid that if I asked they’d say no, that I might be infringing on their part of the world. Yeah. And I didn’t ask and they didn’t offer.

I remember how I felt. So I have an open studio policy. If you want to know me, you’re welcome to visit the studio. It’s encouraged. It’s not proselytizing. You have to visit my studio. If you want to, I would like you to come by. They come by for 10, 15 minutes. They’re thrilled. I mean, who are you painting for? So those who know your work love it. And isn’t it nice to say hello to these people? We don’t offer them tea and coffee. Forget that. But they are welcome to come to the studio and look around.

That’s a very generous thing to do because a lot of artists are very protective of their space, not that they don’t mind seeing people, but they are protective of their sanctuary. So the fact that you have an openness is, I think, very generous. So another question. Can you take us through a “normal” day for you. When do you go to the studio? How do you divide your day between painting and business?

I don’t do anything without breakfast. Nothing happens without my two eggs and coffee. I like that. And the studio is right outside my house. I walk in there and I kind of breathe it in.

I usually know the night before what I’ll be working on that day. If I have to do something like make a phone call or write out a cheque for a bill, I like to just get that out of the way first. Somehow it just nags at me.

Next, I work for 20 to 30 minutes and then I take a break by going into my bedroom and watching TV for 15 or 20 minutes. For me, it’s like a sleeping pill. Nothing shuts my mind down better than the nonsense on the TV. Nothing. And then I go back in and I respond and I paint another 20, 30, 40 minutes, I don’t know. And then when I leave, I’ll nibble on something or I’ll just go and watch TV.

TV works for me like a charm. It really does. It’s all good. Now, I do something called Ask Albert, you get that, don’t you? All right, well that takes some work for me. So, if I didn’t want to paint much that day, I might go to Ask Albert or in the evening, I might go to Ask Albert. But going to Ask Albert is part of it. Basically I’m painting, watching TV, doing something on the computer, eating, taking a stroll or two, and being with Linda.

You met Linda! You came to the studio with Sally from California. Yeah, Sally Strand studied with my friend Burt Silverman in New York. I like Sally and I like what she does.

I love Sally. And when she said, I’m going to Santa Fe to look at art galleries, why don’t you come and I said yes, and we’ll go visit Albert because you’d already invited me to visit. It was fantastic. And so yes, we met Linda.

Would you share your process from an idea through to the finished painting?

It’s done by feeling and the first thing is I make a few lines as to where to start off. It’s placement. It’s not worrying about the light effect. It’s usually trees, rocks, water. And I kind of know where the most important lines are and I put them in first and I have to feel good about it. Actually, I have to feel good about it before I put the lines in. I’ve been doing it so much that I can go like this to the canvas [sways his hands over the paper] and see the paint.

It’s not made in stone. It’s flexible, but that’s how I start. If I don’t see it, I don’t start. So I have to see. I have to feel that way. And I usually don’t miss. As long as I have that [clap]. As long as I’m hit. If I’m not hit, I don’t paint. I’m talking about schlepping around outside.

As far as indoors, you know my studio where I work, I set up the monitor. I work on a lot of paintings at one time and many a time I just pull one out and think ahhhhhh, and that would be what I paint the next day. I always have to have that ahhhh. It’s just work. I don’t mind working, but I gotta have the magic. The ahhhhhhh. Yes. You can quote me on that.

So yeah, I usually have them away so I can pull them out and get a fresh look. And when I get a hit, I’ll leave it out and probably work on the next day or whatever.

I sometimes paint these things when I’m watching television or when I’m talking to you or something. Sometimes I get flashes. What can you do?

That’s interesting. When you say you watch TV, what do you watch? News? Comedy?

No, no comedy. I like documentaries. I get tired of the ads. I watch PBS and all that and if it’s no good, I just go to YouTube. I watch TV and it might be the news. I watch all of the stations from MSNBC to Fox. All of them. I have an Israeli one. And when the ads come on, I just click to another station. BBC is good because they don’t care about Democrats and Republicans.

I remember the first time I came to Santa Fe for IAPS. I think it was in 2001. It was my first IAPS and I was on my own and didn’t know anyone! I had been to Santa Fe before, so I sorta knew my way around and that made it easier. I’d signed up for a number of demonstrations and yours was one. And I remember being kind of flabbergasted by the way you work because when I look at your work, there’s this kind of fresh, spontaneous, very quick, feeling. It’s alive. And yet when I saw you working, I was stunned by how careful and delicate and slow and thoughtful each stroke was. Because for me your way of working didn’t reflect the effect, the energy of the painting. It was really interesting for me to see that.

When I first started, I learned, where does this branch go as compared to that branch and stuff like that. What I’m doing now is there’s a twist to the tree and I go after that. So, I break some color rules with my colour thing that I described to you. It’s just lighter or darker. Different colours of similar value. I’m now interested in the rhythms. In other words, when I do a flutter of leaves and it’s up here, I want to know it’s up here. Does it end here or does it get thinner or get thicker as it comes down. So I look at that. I call it a rhythm, movement. So when you take that into consideration, the twisting of the tree, it proceeds over the measuring. Measuring isn’t the beginning and end. It might be the beginning.

It was also the application of how you applied the pastel in a very deliberate and intentional way as opposed to a fast application. It was quiet. And I remember you didn’t talk a lot. You were intensely involved with the painting. Very deliberate, very intentional. Very particular.

You see pastels, if you vary the pressure, you have more colours. White, if you vary it lightly, it’s much darker. When I do a mountain stream and I press it hard, it lightens more. So I have found that I do this with oils also. If you have a light colour like green, whatever it is, if you hit it hard, you’ve got that green. If you hit it softly, it gets darker.

Same with black and dark colors. If you hit it hard, it’s dark. If you hit it lightly, the dark colors get lighter. So by varying the pressure of the pastel, you have something like this going on. It’s breathing and that’s what you’re picking up on. That’s one of the things.

Light colours look darker. Dark colours look lighter. Rich colours look weaker. You take red, give it a schmear. Lightly, put it on lightly and the red is not as strong as when you give it a shot. So I do that a lot. That’s part of my painting. Understanding that a colour has more to it than that colour. You ought to take a workshop with me sometime, you’d be my guest.

Thank you! I’d be delighted to join you when things open up again. Just going back to what you said about being interested in the rhythm. It sounds to me that you’re always evolving, you’re always learning something new. You’re always finding some new aspect to explore. I’m taking this idea from your use of the word ‘now’ as in – I’m “now” interested in the rhythm.

Do you remember what you just described? That’s part of it. I move the branches around. It’s very flexible. There’s an inner movement of things that really interests me in my subjects. Take a rock face. Eventually, that rock face is going to collapse. The cracks in between the thing which you’re not supposed to give too much attention to, interest me because when the crack gets bigger, it’s all going to fall down. So I’ll never forget this. I was in Taos. I’m standing there and there’s a rock face, not too far. And there was a smoothness and on the floor, I mean it was all right there – the thing that slithered off was laying there. So I put it back together!

I was walking out in California. There’s water, there are beaches, there’s all that. I’m walking and I look down, and I saw some sand and some exposed rock. And I painted it. I want to say this, I’m not trying to be abstract and I’m not trying to be photorealistic. There are some realistic groups that don’t want me – I’m unfinished or too abstract, whatever that means!

I know readers would love to know what pastels and paper you use.

I like to use UART 500 paper. They sell them on boards. I used to use Kitty Wallis paper but she’s out of business.

Pastels? I use a combination of all of them. I have black and white in hard pastels so I can get a crisp line when I want to. Just the black and the white. And I take the label off. I snap it in half. I put the rest back in the box because when you’re painting with pastel and suddenly the pastel’s getting very small, it means you’re using it a lot. You don’t want to lose it. So you go back to the box and it’s there. I buy two of them. So you always have your favourite colours. I use Unison, Schmincke, Sennelier, Grumbacher, Rembrandt. Rembrandt is the hardest of the soft pastels.

I don’t see much sense in making my own pastels because it wouldn’t help me paint better. Let someone else do the work. I just want to grab the pastel.

Any watercolour brand works for the Payne’s Grey. I use oil painting brushes because I’m working on sandpaper.

What are you working on these days?

I do a lot of oils. I was tired of being called Mr. Pastellist as if I’m just right hand. No, I’m left-handed too!

Hey, I like what you wrote about Richard McKinley, about being in his workshop. He’s a good man, a good artist. I liked that blog. It was very, very human. Very human and very informative. You did a great job.

You know, I’m enjoying the isolation and all that, painting like I used to when I was younger.

I have one more question for you and then I’ll let you go. Your signature suspenders. How did that start? Was it from when you were a boy? I think of Albert, I think of suspenders!

It’s the hat and the suspenders! I was overweight at one time and a friend of mine said, you’re losing your pants. You know, I had a beer belly. So I wore these. And when I was up in Alaska I went painting with my friend Richard Schmidt. And up there, it’s rough. It’s rugged, you know. And the fishermen, wear these fatter ones and I loved them. They had orange ones but they stopped making those. So I went to the red ones. Along with my black Greek sailor’s cap, they are my entrée into fashion.

I’m a little bit casual with my dress. For me, when I go to the California art club, the gold medal show, you don’t just walk in, you gotta be, you know, dressed. You don’t wear dungarees so I dress up for that.

~~~~~

Wowsa!!

I think this blog may take a few repeat sessions to absorb!

Albert Handell and I hope you enjoyed it thoroughly and we’d LOVE to hear your thoughts and questions so fire away in the comments below!

By the way, check out the interviews I did with Albert Handell at the 2017 IAPS Convention. Click here to see them. There’s one at the start and then scroll down to find the second one.

Until next time!

~ Gail

PS. I wrote about one of Albert Handell’s masterful paintings of rocks in one of my monthly roundups.

PPS. Here are a few of Albert Handell’s books:

And here are the earlier books that Albert Handell is a part of:

34 thoughts on “Albert Handell – Moments in Time”

Thanks you so very much for this wonderful read. I have always loved Albert Handel’s work. Years ago when I was in Santa Fe, my heart place, taking a class with Richard McKinley he took us to visit Albert’s studio. Albert wasn’t there but his creative energy was. It was an experience I will never forget. I haven’t worked in pastel for a while. After reading this interview I will return with fresh eyes.

I’ve been working in acrylic and it doesn’t have the same effect that I once had when I was a pastelist.

Thank you for much for this inspiration.

Next time I go to Santa Fe I will visit Albert Handel’s studio again.

Connie, thanks so much for sharing your experiences with Albert (and Richard!). How wonderful to feel Albert’s energy in his studio although he wasn’t in at the time. (And what a treat to be taken there by Richard!) I LOVE that Albert’s interview has inspired you to get back to the magic of soft pastels.

Of course, Albert himself switches back and forth between oils and pastels so it is possible to work in two different media (separately). I also work in acrylic and I like the balance between splashing about in paint and the linear and sumptuous colour and application of soft pastel!

What beautiful art and what an interesting artist. I appreciated his thoughts for students on practicing and on taking time to step back from a painting or paintings and look with fresh eyes. I would like to know more about and try the watercolor approach he uses.

Thank you so much, Gail, for sending this.

Joy

So happy to hear how much Albert’s words and art spoke to you. (Remember, as an IGNITEr, you can watch the interview in its entirety! And I think looking into the use of watercolour as an underlayer is in the cards…😁)

Yes, there are many nuggets to explore in this piece. His work makes me ‘sigh’ with pleasure.

Sighing with pleasure says it all Marsha!!

Reading this, I was so appreciative of hearing a master say, it’s the practice. I’m a violin teacher in addition to being an artist, and it annoys me too, when people think that they can just snap their fingers and be able to do something without years of daily practice. And as if they don’t have instant talent, it is a useless endeavor. So not true! But you must be willing to put in the time!

My question refers back to the painting where the payne’s grey watercolor was added later in the studio. My experience with adding water/alcohol to a pastel painting is a huge change in texture and somehow activating more brilliance and depth or contrast by filling in the tooth. I understand a watercolor wash prior to pastel application, and it’s peeking through. I guess I’m flabbergasted at how he added a wash later with such a cohesive look! Any insights?

Yeah – practice practice practice! I think so many people think they can skip that part….is that part of our instant gratification culture?? Cool that you teach violin Sue. Wish you could play us a wee something right here!

And oh my word, I’m so glad you asked that question about applying watercolour after the piece is finished!! I’ll look forward to Albert’s answer too. However he did it, it sure was effective!

Thank you both for this post. I took time to read it carefully, it contains so many insights, and the images fit so well. Like a good reference book, I’ll be coming back to this often.

Eileen that’s so wonderful to hear! We worried that it would be too long but I like that it’s all together like, as you say, a reference book.

And thank you for your appreciation of the images as I do take time with image selection and placement. I’m so thankful Albert had so many older pieces available digitally!!

Great interview with Albert Handell. I have had his book ‘Painting Landscape In Pastel’ – it feels like I have owned it forever. It’s like a Bible to me. My dream would be to take a class. That is highly doubtful.

It was so interesting to read about his life in NY, Manhattan, Brooklyn and Woodstock all I’m familiar with.

He is one of the last iconic artists of his genre, I bet it would be hard to find another with his life experience.

Thanks for the interview. I’m going to remember what he said “paint every day “

Glad you enjoyed it Sandi! I think many of us have at least one Handell bible lol!

And yes to his advice…PAINT EVERY DAY!!

Your interviews are all good Gail, but this one, for me, is one of the best. I was unfamiliar with Albert and his work, but what a find, so thank you for that. There’s so much good stuff to take away from this! I wish I lived nearer Santa Fé…

Ohhhh I’m so glad you now know this artist’s fabulous work Morag!! And delighted you enjoyed the interview. It did wander a bit but I think that’s part of its charm.

I think many of us wish we lived closer (or in!!) Santa Fe. It’s a very special place that’s for sure.

I studied with Albert Handell many years ago in Woodstock. It was a changing point in my career as a pastellist. For many years, there were few teachers of pastel. I learned so much from him. He was working on industrial sandpaper before it became easily available as an artist’s surface. I also studied with Daniel Greene, also an amazing artist, but I felt that Albert was a better teacher, more sharing, and caring. At 89 I am still loving and working in pastels.

Carol how marvellous that studying with Albert all those years ago in Woodstock had such an impact on you as a pastellist! And thanks for sharing your kudos on Albert as a teacher. I’m sure he will be warmed to read this!

This man has so many facets he’s a diamond! Please Gail take him up on his precious offer and then do give us more! When I was young and thinking about furthering my art my desire was to paint with a blend of realism and abstract. Albert is the master of this!

Thank you Gail!

A diamond indeed! Great analogy Brenda. And yes, I love that idea of taking up Albert on his generous offer and then sharing my learnings with you here. Now to just figure out how and when to make that happen….

And you’re right..Albert does combine realism and abstraction so brilliantly!

Gail this was a truly charming and informative interview— I loved it!! You are right, there is enough here for multiple sittings, you’ve captured a wonderful record of an artist we all admire. Thank you for sharing this with us!

I’m so glad you found it so Louise!! It would have been a shorter read if I’d cut out more but there is so much of Albert’s “voice” and personality that comes through that I just had to leave it all! I’m honoured to have his words and work here on the HowToPastel blog!

Hi Gail,

Thanks for such a great, in-depth interview with Albert. I took a pastel workshop with him in Cambria, CA last May. It was fantastic. He has such a wealth of knowledge and I learned so much in 4 days (although I didn’t know he was a dancer or about his interest in TV). He promised to cover everything about pastels and he checked all the boxes. His demos were amazing and his critiques were very honest and encouraging. He showed us his simple watercolor and pastel alcohol wash under painting techniques. He also stressed not worrying about finishing a piece but rather making sure that the center of focus is done correctly. His composition and ability to focus in on a detail within a scene, and use of light, shadow and colors are amazing. It was great to see a piece of his go from start to finish in only 2 hours.

Hi Marc, so glad you enjoyed the interview. (I knew about Albert’s love of dancing as I’ve enjoyed dancing with him at IAPS!)

Thanks for sharing your very positive experience with Albert as a teacher – makes me want to attend one even more! And thank you too for sharing a couple of nuggets that you came away with – like the part about not worrying about finishing – that’s a biggie!!

Gail, thank you for posting this, I so enjoyed reading it. It’s so wonderfully wide-ranging and captures his personality and approach to painting so well. I feel like I’ve just spent a half hour at a cafe table with him myself, what a pleasure. Great questions, really interesting.

Ahhh what a lovely way to put it Jeanne! And that’s indeed what I hoped the impact would be – an easy-going chat with Albert. So glad it has that feeling!!

I believe I saw your previous interview with Albert. I was fascinated by his NY personality which brought back so many memories for me. This written interview took two sessions for me to read completely, but it was well worth it. Very informative and thorough. Every time I thought of a question, you asked it. And Albert is so generous with his answers. Really enjoyed it!! Thanks Gail!!

So glad you had a second time enjoying it Ruth (and yes, you would have seen the video interview in IGNITE!).

The post is long indeed but I felt rather than split it into two posts, it was better to have the whole interview in one place as a resource to go back to.

It tickled me to read that every time you thought of a question, I asked it! Whoo hoo! And yes, Albert was soooo generous…with his answers AND with his time!!

I am so glad this was a loooong read. Every paragraph, every sentence was good. I feel immersed in something, and that happens so rarely online. Please do not hesitate to go long!

Ohhhh that’s soooooo good to hear Chris! Thank you for confirming what I felt about keeping this interview whole and also in one post. I really appreciate hearing this!! I love that it was an immersive experience for you, kind of like what Jeanne said earlier about spending time with Albert chatting in a cafe. Fantastic! Thank you!

Gail,

Thanks so much for the Albert Handell interview. He is an amazing artist and I’ve only had the privilege of viewing a workshop online with him. I was encouraged by his advice to paint daily and not worry about finishing- just trying to solve the problem. It encourages us emerging artists to just keep showing up ! Your questions were right on Gail , thanks so much for a commendable interview!

I’m so glad this resonated with you Jan. Thank you for sharing how his encouragement and advice impacted you as an artist!!

Wow. Wow to the artist, to his work, to your interview and the wealth of information from it. Wow.

Barb, thank you for all your WOWs!!!

This is such a wonderful interview Gail. I felt like I was sitting with you! So many moments made me laugh (pastels in order make my eyes go to sleep). There are so many gems I know I’ll reread this again. Having taken a workshop with Richard McKinley, I can see Albert’s influence in the way he applies his pastels so slowly and thoughtfully. This interview was like a mini workshop!

I know right!!?! To all you have said.

(And as an IGNITEr, you can watch the actual video interview in the “Blind Date” section!)