I had decided it was time for another ‘Close Look” blog. A number of possibilities came to mind but as I began preparing, I realized it was almost Remembrance Day. So it made sense to choose work related in some way to war. I began to recall pastel portraits I’d seen somewhere along the way, pastels of soldiers, sailors, and airmen. I began to dig and soon I was rewarded with a name – the British artist Eric Kennington (12 March 1888 – 13 April 1960). And oh yes, his powerful, expressive pastel paintings!

And so it was decided – I’d share three of his portraits (three because I just couldn’t choose one of them!). The first two are done in 1940, the third in 1941. During these years, Kennington worked for the War Artists’ Advisory Committee (headed up by Sir Kenneth Clark) and then the Air Ministry, painting numerous portraits. (In 1942, 52 of his RAF portraits were published in his book, Drawing The RAF: A Book of Portraits.)

Eric Kennington captured not only the physical characteristics and confidence of these three service men, he also revealed the essence of their being, albeit in an idealized way. I look at these portraits and, oh my gosh, I can almost imagine what each man might say if I spoke to him, the things others might say about him, the behaviour he might exhibit. With so little, the artist says so much about these individuals.

As you’ll see, Kennington worked effectively with a limited palette of colours. He let the colour of the paper (a middle value warm neutral colour in all three cases) become an intentional part of the whole. He was an excellent draughtsman, rendering the anatomy and various parts of the face, body, and clothing in a three-dimensional believable space. This comes from knowledge and working from life.

Since I’m including three examples, I’ll only select a few things about each to focus on but I encourage you to look closely at all the various parts.

Let’s look at the first portrait.

Eric Kennington, “Portrait of Stoker A. Martin of HMS Exeter,” 1940

You’ll see in this portrait how much Kennington utilizes the colour of the paper. This ability takes a deep knowledge of value and of colour and how they work together.

Below, you can see this clearly at work. On the right side, where the light hits the hat, there’s not much to be seen of the paper. In the middle part, as you move towards the left, more and more of the paper is visible until finally, you encounter untouched paper on the hat’s shadow side.

Interestingly in this portrait, Kennington leaves much of the background untouched except for one area behind his subject. Why include this strip of pastel? Can you see how it anchors the subject in space? It gives it a context. It also pulls the blue seen in the man’s eyes and in the fabric on the collar, and thus relates the subject to the background. You can also see how Kennington sometimes brightens the area of transition between subject and background. This subtly pushes the subject forward by emphasizing the edge.

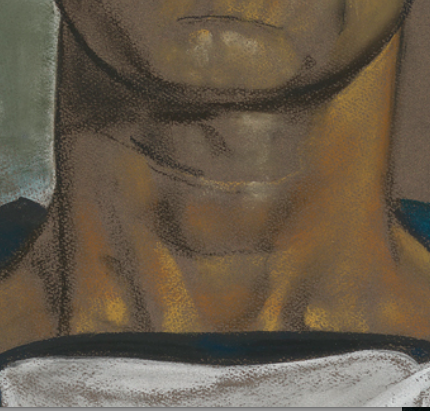

I’m in awe of the neck. I find this generally a tricky area to paint, to find the balance between putting enough in to make it read as neck and not too much which over emphasizes it. Here the neck takes up a large area of the portrait yet we aren’t distracted by it. Kennington successfully manages to relay the anatomy without drawing our attention to it. In fact, if you weren’t an artist, you may not even remark on the neck! Look closely to see how little pastel is applied, how the artist leaves much of the paper untouched, and how light and shadow are shown. And yet note also how much of the muscles, tendons, and adam’s apple are revealed.

Another area where Eric Kennington utilizes the paper effectively is in the clothing. Have a look to see just how the artist uses pressure on the white pastel to either obliterate or leave the paper to read as the shadowed area of cloth.

Eric Kennington, “Flight Lieutenant Lloyd Watt Coleman, DFC,” 1940

Now let’s have a look at the second portrait, also done in 1940.

You can see immediately that this portrait is done on a smoother paper. (The texture of the previous portrait makes me think of the gridded side of Canson Mi-Teintes paper.) It almost gives the appearance of blended pastels but look closely and you’ll see it’s not blended after all. It’s more to do with the pressure of the pastel and how much of the paper comes through. Have a look at the cheek and ear lobe below.

And what about that nose!! Brilliantly done. You can feel the fleshiness of it with the bone beneath the bridge. Look at how impressively Kennington used a limited set of colours!

Now have a close look at this one eye. I could admire it for ages!! Look at the way the light catches the inner and outer parts of the eye socket, the brilliant highlight and the subtle shadowing on the eyeball, the green that glows from the iris, the red-tinged lower lid, the barely indicated eyebrow. There’s soooooo much to study here!

Now let’s have a look at the very restrained way Kennington indicated the clothing and insignia. So little is shown yet we easily read what all the bits and pieces are meant to be.

One of the things I found interesting was the stripe of yellow pastel Kennington applied to show light on the sliver of neck seen on the left side. Look at the whole portrait and it fits right in, look at it closely and it seems a bit out of place. Somehow he made it work! One thing to notice too is how well it’s balanced by the light strip of hair diagonally opposite.

Eric Kennington, “Pilot Officer M J Herrick, DFC,” 1941

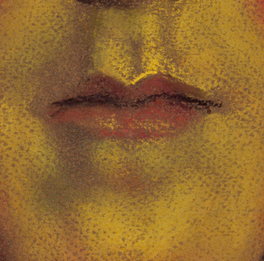

Now let’s have a look at the third portrait. Done in 1941, it returns to a more textured paper. Eric Kennington used colours on the face that are a lot brighter and warmer than those in the portraits above. They reveal a youthful glow and perhaps a person who spent a lot of time in the sun.

The sitter has no hat this time so we can see how the artist dealt with the hair. It looks as if Kennington applied the colour lightly, using the texture of the paper to reveal the lighter parts, and then applied more pressure to the pastel stick for the darker areas. You can also see the line of brilliant blue the circles the head, bringing our attention to the edge where hair meets background.

Kennington used an olive green colour over both skin and clothing. On the skin, it shows the shadow side of the face, in the clothing, it shows the colour of the fleecy collar. In the former, it acts as a darker colour, in the latter, it acts as a lighter colour. This is a great example of relativity. The colour takes on a perceived value depending on what it’s next to, the amount of area it takes up, and the physical thing it is representing.

I’m fascinated by the way we receive so much information about this subject’s mouth and the way it sits in the face, with so little pastel information. It’s all about pressure and knowing where to place emphasis or not. You can again see how Kennington used the paper to his advantage. I love that he didn’t fuss with the line that separates upper and lower lip.

The background is blue and echoes both the shirt and the sitter’s blue eyes. It’s also a nice contrast to the orange-reds of the skin.

And finally, let’s look at all three sets of eyes together. None of them look out at the viewer. This gives the feeling of detachment, of the subjects being in their own worlds. Study these if you’re keen on doing portraiture!

Brave men and women serve in the military, the navy, the airforce, ready to fight for us and others when they are needed. These portraits by Eric Kennington give us a look at three men who fought for Britain in World War II. They’re individuals whose characteristics and personalities pulse through the years, inviting us to get to know them decades later.

As I said, because I didn’t limit myself to only ONE portrait, I didn’t go into all the details I could have shared for each portrait. So I’d love to hear about the things that strike you, particularly anything that I didn’t mention! Let’s call them portraits A, B, and C as an easy way to refer to them.

I very much look forward to your comments!!

Until next time,

~ Gail

PS. To see more work by this artist, visit the National Portrait Gallery (UK), the Imperial War Museum (UK), and the Tate Gallery. At the Tate, see especially the fabulous portrait of Mutter Il Hamoud Min Beni Hassan done 20 years prior to the portraits in this blog. Eric Kennington met T.E. Lawrence (of Lawrence of Arabia fame) and some of his work was used to illustrate Lawrence’s book, The Seven Pillars of Wisdom, for which Kennington acted as art editor.

This book looks fantastic but I haven’t previewed it yet!

32 thoughts on “Eric Kennington – Three Portraits For Remembrance Day”

Wow! talk about less is more! These are masterful! Thank you Gail for pointing out all the incredible qualities of this artist’s work! And thanks for introducing him to me, had never seen his work before. You are so right about there being a lot to study. Brilliant blog!

Jan thank you!! I’m so glad you appreciate them as much as I do. They are indeed masterful!!

This a moving idea Gail to ally history with painting today.

-I scrutinized with great interest the three portraits as I just entered a workshop dry pastel portrait with Société des Pastellistes de France in Paris.

Your detailed study of those portraits drove all my attention because I have to say I am a little lost in that workshop where others have more or less ong experience and I, a full novice.

– that use of the color of the paper integrated to the painting gives such strength

-I noted that the choose of the side of the Canson is volonteer when as to the gridded side which could give a more illusive character to the portrait.

I was interested by your stress of the pressure of the stIck, the no “fussing” with the line of the mouth.

– you did not mention both uses of pencils and sticks but I think I did perceive it.

– which puzzles me is as you is that none of the subjects look at us . This is masterly rendered but how? I have to scann those three looks Closer quand Closer to pierce the secret. It must be all In shadows and light.

Thanks So much Gail for that sofruit full study.

Geneviève thank you for your full and detailed comment! I love all the things you point out, noticed by looking closely at the work.

keep looking, keep studying, keep painting.

Merci beaucoup!!

Thanks Gail I love your blogs I am in awe with your beautiful work. I read them over and over!!

Thanks so much Carolyn!!! That’s just so great to hear 🙂

Thank you for this excellent and very appropriate collection of work. I hadn’t seen Kennington’s drawings before but they are so emotive. The strength of character of his subjects is immediately apparent. There is also the feeling that in his drawing of the eyes, we sense that they have seen things no one should have to see. Very powerful artistry…

Yes David!! I LOVE what you say about the eyes. It’s as if they won’t look straight us otherwise we would know what they have seen. So glad you enjoyed these and hope you take a look at more by clicking on the links at the end of the post.

Gail, such an interesting blog today. I would never have thought to combine the remembrance with old portraits. Brava. And they are so interesting. J

Thanks Jody! It was a fun challenge to do this and interesting how it all came together. I was thrilled t be able to share these amazing portraits!

Gail, such an interesting blog today. I would never have thought to combine the remembrance with old portraits. Brava. And they are so interesting. J

So glad you enjoyed this blog Jody! I had a totally different plan for it before I dinged that it was Remembrance Day coming up. I think this was a way better way to go 🙂

These 3 pieces really show how much the artist uses the paper as part of the portrait, really a ‘support’. Thanks for pointing out such subtle details like those parallel yellow lines! I always learn so much from Your critiques!

Yes, he really knew how to incorporate the colour and value of the paper as part of the whole!! I LOVE looking closely at work and making discoveries I otherwise wouldn’t have – like that crazy strip of yellow! So good to hear you learn lots Helen 😀

To me these portraits are a superb example of how to really ‘look’ at your subject, painting what you see not just what you assume you see. Looking at the painting of Richard Hillary (NPG) his somewhat unorthodox treatment of the eyes and the subtlety of the lines around the mouth and jaw evoke the restless energy of his subject. They really have something a bit magical about them. Thank you Gail for showing them here, wonderful.

Exactly Morag!! Thanks for your comment about Eric Kennington’s portrait of Richard Hillary in the National Portrait Gallery! You are so right about the restless feeling. Love also that crinkle on his brow just above the eye.

So happy to hear you enjoyed them!

Not being much of a portrait fan, I probably would not have given these a second glance if they were anywhere other than your blog. My loss, obviously! The way he uses the paper is some special kind of genius I have not seen before and my mind is delightfully spinning trying to figure out how it could be done. I don’t know which is more astounding to me, Kennington’s masterful work or your sharp-eyed and insightful commentary. What an educational and inspiring way to start my morning! Thank you Gail….

And what a delightful way to start mine Leslie!! You are so right about his genius in using the paper as part of his work! I think trying to copy even parts of his portraits would help us all in incorporating the paper colour into our paintings.

This was really timely and useful! I love how you cut the images up to get us to look at the different parts of the portraits! Portraiture is my first love and this was very helpful!

Thanks!

Maureen Gerrity

Great to hear Maureen! Enlarging and separating a piece of the painting away from the whole I think really drives whatever point I’m making home. So I’m glad to to hear that works 🙂

I didn’t know that about you and portraiture. I’ll look for your portraits!

I always learn so much from your analyses of various artist’s work. So many great things to learn from the close up study. The thing that struck me, more than his expert technique with paper and pastel, is the eyes of those veterans. As David Wells said above, you can only imagine what those eyes have seen. I feel a deep sadness in all of them. Beautiful, emotional portraits. Thanks again Gail! Another fabulous blog.

Ohhhh Ruth, thank you for your kind words. And yes, it’s the eyes that keep you looking and looking in the end. Such stories lived that can only be imagined by us….

This was very interesting and informative. I want to begin studying how to do portraits, so this was helpful.

Thanks so much

That’s fantastic Karen. I love good timing 🙂

I am interested in the amount of yellow-gold in their complexions. I am not a portrait artist (though I would love to be) and the combinations used for the skin colors seem so counterintuitive to me. I suspect that the colors relate to the mood, but I cannot really understand how they all work together to look totally believable.

It’s intriguing isn’t it? One thing is that the yellow-gold is a light value and so can stand in for those areas light. Perhaps the artist had limited choice of colours (during the war especially?) and he would choose to use the warm colours for the skin and hair rather than layering in blues and greens. And I think, to answer your question about how they work together so believably, you could look to value! You can see the portraits in black and white at the top of the blog and see how they read without colour.

Great idea to honor our veterans.…!

😀

Thanks for posting these wonderful portraits. The thoughts seen in these men’s eyes are loud and clear. So well captured too.

You are so welcome Diane! Yup, those eyes…..what they have seen….

Excellent commentary Gail…I’ve seen these 3 portraits before (on line) and you made me enjoy them all over again…only even more!

Thanks so much Jill! I’m glad I could help you see them again perhaps with a deeper look…